Franklin:

A Ghost Town at our Doorstep

A Ghost Town at our Doorstep

Several communities surrounding Enumclaw got an early start with the discovery of coal, as indicated by place names such as Black Diamond and Carbonado. (During the boom times, Black Diamond was the third largest city in Washington, and Carbonado had a population of 3000 when Enumclaw had only a few families.) California investors developed the Black Diamond mine in 1864, and in 1872 Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University, opened the Carbonado mine. Up to 85% of the coal from the Puget Sound region was exported to San Francisco during the late 1800s, helping it to become the dominant city on the west coast. As early as 1882, fifteen shiploads full of coal were traveling from Seattle to San Francisco each month.1

Out past Krain and Veazie at the end of the Enumclaw-Franklin Road, the Oregon Improvement Company, a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific Railroad, created Franklin as a company town around new mines next to the Green River. The first coal came out of the tunnels on July 28, 1885.2 Five years earlier, the Oregon Improvement Company extended its railway to Franklin, paying Chinese laborers 80 cents a day. The narrow gauge track dead-ended at the Green River Gorge with no turn-around, so trains had to back all the way into Franklin from Black Diamond.3 Coal is the reason railroads were built so early from Renton to Black Diamond and Tacoma to Wilkeson (and the reason the first Plateau settlers could find supplies in Wilkeson.)

Once mining at Franklin was underway, word spread, especially in Europe, and many immigrants from coal-mining areas there came here, so the new mines had a ready supply of skilled labor. Many of the farmers from Krain and Veazie were already veteran coal miners from Europe and found work in the Franklin mines, while their families raised produce to sell there. (In the early days, to get to Franklin from this side of the river, you climbed into a small basket suspended from a cable and pulled yourself across the gorge.) By 1902, our neighboring ghost town of today had a population of 1,000, with a school, two general stores, three barber shops, a Post Office, three hotels, two meat markets, four lodges, and a saloon, so it provided a good market for the cash-strapped farmers.4

A few years after the Franklin mines began operating, labor troubles developed. Following a new contract with substantial wage cuts, workers staged a major strike in 1891. The mine superintendent traveled back to the Midwest and recruited 300 black laborers with a promise of good pay and working conditions, as well as company housing. They were not informed that they were being hired as strike-breakers.5

The recruits and their families were transported by train to Palmer rather than

The recruits and their families were transported by train to Palmer rather than

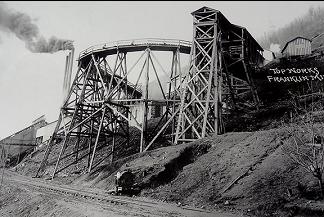

Franklin mine fan house

Black Diamond, since the company expected trouble there. After arriving, each of the men was given a rifle. Asking why they would need guns to mine coal, they were told they might encounter wild animals and Indians on the walk through the forest from Palmer to Franklin.6

Later, another train arrived from Newcastle, and striking miners fired on it. The armed blacks assembled on a hill overlooking Franklin and the battle began. At least one white miner was killed and several were wounded. The state militia was called in, and things calmed down, or at least simmered under the surface.

The superintendent at Franklin later said the company "made the issue one of race between the white and colored miners, and not one of wages and conditions of work between the coal companies and their employees." 7 Tensions eased somewhat after the United Mine Workers of America established an integrated union at Franklin.

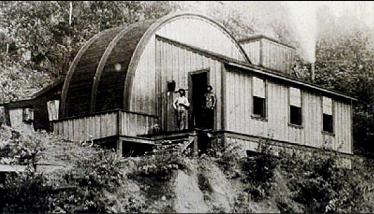

Don Mason leads a Frankllin tour.

On August 24, 1894, the second-worst mine disaster in state history occurred at Franklin, killing thirty-seven miners. According to some accounts, an inquiry revealed that the fire was intentionally set and that the perpetrator, unable to escape the toxic smoke, also died.9 In other accounts, the fire started accidentally and was under control, but the mine fan was mistakenly shut off, suffocating the miners.

Franklin was officially disbanded by the Oregon Improvement Company in 1919, although some mining continued and a few residents remained. Edwin Moore's family was among them. His grandfather was born a slave in 1846 and was one of the original mine recruits. Edwin, born in Franklin in 1912, finally left in late 1930s, and wrote his grandfather's story, A Coal Miner Who Came West, in 1982.10

A coal seam at Franklin

Franklin today

Special thanks to the Black Diamond Historical Society for their tours and pictures.