History of the

Anderson Garden in Enumclaw

Anderson Garden in Enumclaw

Her last major outing in May of 2007 was to an Enumclaw Garden Club luncheon held here in the garden, where she had a wonderful time visiting with many of the friends she had made over the years. While at Expressions, we found ways to take the garden to her, with a Lavender and Ladies event, a Blueberry-Bluegrass party, daily bouquets of sunflowers. When she died that September, we held a celebration of life here in the garden, where guests watched a slideshow of her 95- year life. When we first moved here, many of the rhododendrons were obscured with berry vines and tall weeds. We spent some years clearing them out, and then added several new features, including a native garden, herb garden, bamboo forest, and azalea orchard. In the process, we added or replaced about 1,000 plants. Seventeen years ago, we started a website that now contains several thousand pictures, and has had half a million viewers from 155 countries. The "peak" is usually the middle of the month. Enumclaw became a destination for more than 1,000 garden visitors from around the world each year. Four times, the American Rhododendron Society has brought busloads when its annual convention was held in our area, the most recent in May, 2013. Garden clubs, Red Hats, art classes, and many groups have been also regular visitors. A Mother's Day stroll is popular with visitors. We're continuing that tradition and maybe we will see you here this year.

RESOURCES

The Anderson Garden Website

Betty Anderson Slideshow

65 Garden Benches

A Trike Ride Through the Garden in Bloom

RESOURCES

The Anderson Garden Website

Betty Anderson Slideshow

65 Garden Benches

A Trike Ride Through the Garden in Bloom

Resources

About

Contact

Why did someone with successful nursery in a New York City suburb decide to start all over, late in life, 3000 miles away? Why would a teacher in an ideal setting and a decade away from retirement, want to give that up and begin anew in an unfamiliar little town with a funny name?

How did the Enumclaw rhododendron garden of today grow out of the hayfield of 50 years ago, and WHY?

Well, my father, Bob Anderson, was reading a book about dirt (not a best seller) in the 1950s. It raved about Buckley loam. So he did what any of you would do--he got on a bus to Seattle, from there to the bus stop at Mel's Confectionary in Enumclaw (the last independent Greyhound agency in the state), and finally walked over to Buckley. It looked just like what he wanted, so he walked back across the bridge and began making plans. But since the return bus was late in the day, he spent the afternoon wandering the streets of Enumclaw, and decided this would be our new home.

Actually, the story goes back further than that. My father wanted a good place to grow rhododendrons, but how did he get into that? In 1905, his father, John Anderson, was hired by Gifford Pinchot, founder of the U.S. Forest Service under Theodore Roosevelt and namesake of the National Forest up the road from here. Pinchot sent him to Washington state, among many other places, to promote the novel idea of conservation in the nation's forests. When Pinchot lost his job under Roosevelt's corporate-friendly successor William Howad Taft, so did my grandfather.

Gifford Pinchot

and Teddy Roosevelt

and Teddy Roosevelt

He could have settled here, but instead chose Appalachia, where Bob was born. Through his talks, he had gotten to know many of the farmers there, and they had a real problem with rhododendrons. Their cows would chew these native plants sprouting up all over their pastures and get very sick. (The rhododendrons also got very bushy and beautiful with their bovine pruning.) So they made a deal. My grandfather could clear out and take as many plants as he wanted and ship them in boxcars to New Jersey, where he would sell them.

Bob Anderson was born in Black Mountain, North Carolina, and spend his first several years there.

That necessitated a moving his family to the Garden State, where my father grew up. My father studied landscape architecture at Penn State and was lucky enough to land a job at the Thomas Edison estate after graduation. He took his earnings and toured the gardens on Europe on a bicycle and then bought eight remote New Jersey acres to start his own. (My grandfather thought he was irresponsible going into debt during the Great Depression.)

After the war, my father started a rhododendron nursery and built a family home out of stone from the place. We got electricity (and an electric pump for the well) just before I started second grade. In many ways, it was an ideal setting for everyone. My mother enjoyed teaching school nearby, my father could grow and sell his rhododendrons, and continue his painting, with two trips a week to the Art Students' League in New York City. I could play in the surrounding forests and hunt deer with by bow and arrow.

But then we started taking camping vacations out west, and everything changed. Our favorite destination was Mt Rainier, and in time became the focal point of these trips. Of course, this meant passing through Enumclaw and seeing the Buckley loam. It seemed like a perfect spot to raise rhododendrons, with that black topsoil and hospitable climate.

Mt. Rainier was our favorite destination on the summer trips from New Jersey.

My parents met Herb Sorenson and Jack Thim, both from Enumclaw pioneer families, who encouraged us to come, and sold us twenty acres out by Veazie. But my mother put her foot down. She wasn't excited about moving across country anyhow, but was definitely tired of living in the wilderness, albeit a New York City suburb. As a compromise, within a couple of years they bought the five-acre hayfield on Roosevelt Avenue. That gave my father enough room for his plants, and my mother a closer proximity to civilization that she had even in New Jersey. Several years before our move here, my father began moving plants across country to Herb and Jeanne Sorensen's farm. He also built some propagating frames to further build up stock, entrusting their son Mason to tend them. Since the hayfield was empty, we needed a place to stay before our house was built.

One evening, Jack Thim called and said he had found the right house on the corner of Roosevelt and Lorraine, a few blocks from the future garden. My father bought it over the phone, sight unseen.

Our Enumclaw home for the first year

New York City was as close to us as Auburn is to Enumclaw. My father painted there twice a week.

The Anderson Garden in New Jersey

The next June (1961), my father headed across the country on a second trip in his 55 Dodge truck, this time with all our belongings under a canvas tarpaulin, like the pioneers in their covered wagons. I graduated from high school a week later, and my mother and I drove the car on the same route. We were eager to settle in, but our renters weren't ready to leave, so we spend the first month in Jack Thim's cabin on Lake Sawyer. As soon as we were settled on Lorraine Street, we started work on the garden. First we moved the plants and cutting frames from Sorensens'. I remember cleaning Christiansen's barn behind our field and spreading manure on the hayfield with his tractor. We immediately got to know Andy Berilla on the farm across the street. My father gave him rhododendrons to plant on his side of Roosevelt. Andy had retired from farming, but still had what seemed like thousands of rabbits for the neighbor kids' amusement. Herb and Anne Forler both worked at the Weyerhauser mill and lived in the little brick house he built next door. He and Andy shared their family stories and history of the area with my parents.

Herb Forler explained two unusual carved sandstones in the hayfield--grave markers for Japanese mill workers from the turn of the century.

In September, I headed off to Whitworth College. My mother began teaching fifth grade at J.J. Smith School, and my father designed our house and drafted the garden plan.

In the spring, he contracted with builders Jensen and Peterson and by the following summer, we moved in. I remember dividing my time that summer between working at the end of the Farman Pickle Factory assembly line and chipping mortar from old bricks from an old Wilkeson coke oven for the new patio. Fall semester at Whitworth couldn't come soon enough. Always frugal, my father decided to sell off an acre to reduce frontage on Roosevelt. He worried the sewers would be extended and incur a huge assessment. (They haven't come yet, 50 years later.) Pete Kranz, one of the Enumclaw Food Center owners, bought it and built a house to raise his family. The gregarious Pete was also a treasure trove of old stories about the old days of the town.

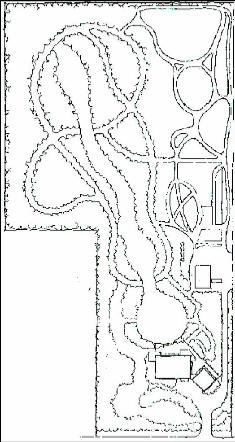

The garden grew gradually. Each year, my father developed another hundred feet or so until he finally reached the old fence at the adjoining farm at the back, 660 feet from the road. Milt Allen, grandson of pioneer John Barnes (who had cleared the stumps out of Griffin Avenue with his oxen), put in our rambling lawn. Eventually, the garden held more than 3,000 rhododendrons, with more than 100 different species and 300 hybrids, complemented by numerous companion plants and trees.

My father and mother had more than 30 wonderful years in the garden.

Eventually it became too much for my father to take care of. But as his body and mind became frail, my mother kept him here for several more years. Despite the risks, she thought it better to keep him in the garden he had created as long as possible. Near the end, he would fall quite a bit. One day elderly neighbor George Richardson and some friends found him on the ground near the back. Unable to lift him, they grabbed a wheelbarrow and brought him back to the house. George said my father grinned with delight throughout his thrilling ride, shortly before he died in 1994. The

garden was too big a responsibility for my mother alone, so Doreen and I moved here in 1996. My mother moved to Emerald Court and lived there the next ten years, then spent a few months at Expressions.