A History of Logging and Lumber

in and around Enumclaw

in and around Enumclaw

About

Contact

The lumber industry in Washington peaked in the latter half of the 20th century, but its days were numbered. With most of the virgin timber gone, public lands were closing down to preserve the few old growth trees that were left. The large companies began looking for cheaper and easier places to farm trees, such as the southern states and developing countries. And with much larger reserves, Canada became a major competitor for local mills.

However, another global trend softened the impact of these changes for Weyerhaeuser and the gyppos: a burgeoning Asian market. First it was Japan, followed by China. The surviving but greatly reduced local industry was kept afloat by the export market, and then by the domestic housing bubble of the early 2000s, until it crashed in 2008. That was the final blow, and in April of 2009, the White River mill closed its doors for good after more than a century as an integral part of our community. (7) But even that did not end logging in Enumclaw. For a few years, a yard on highway 410 in Buckley still stuffed local logs into containers bound for China, brought to them by persevering Enumclaw gyppos and log truck drivers.

Today the history of Enumclaw area logging is celebrated with a bronze sculpture of an oxen team pulling a huge log out of the woods. Located in front of the library, this locally sponsored piece is testament to the 125-year role of loggers in our community.

---------------------------------------------

NOTES

1. Nancy Irene Hall. In the Shadow of the Mountain. The Courier Publishing, Enumclaw, 1983, and republished by Heritage Quest Press, Orting, 2004. p. 107.

2. "White River Lumber Company". Historylink.org. Essay 414.

3. Louise Poppleton. There Is Only One Enumclaw. 1995. p. 43.

4. Poppleton. There Is Only One Enumclaw. 1995. p. 45.

5. "Final Logs Roll Through Weyerhaeuser Mill". Kevin Hanson. Enumclaw Courier-Herald. April 30, 1990.

6. Use of Articulated Wheeled Tractors in Logging

* Current discussion of the Garrett Tree Farmer: Forestry Forum

7. "Final Logs Roll Through Weyerhaeuser Mill". Kevin Hanson. Enumclaw Courier-Herald. April 30, 1990.

However, another global trend softened the impact of these changes for Weyerhaeuser and the gyppos: a burgeoning Asian market. First it was Japan, followed by China. The surviving but greatly reduced local industry was kept afloat by the export market, and then by the domestic housing bubble of the early 2000s, until it crashed in 2008. That was the final blow, and in April of 2009, the White River mill closed its doors for good after more than a century as an integral part of our community. (7) But even that did not end logging in Enumclaw. For a few years, a yard on highway 410 in Buckley still stuffed local logs into containers bound for China, brought to them by persevering Enumclaw gyppos and log truck drivers.

Today the history of Enumclaw area logging is celebrated with a bronze sculpture of an oxen team pulling a huge log out of the woods. Located in front of the library, this locally sponsored piece is testament to the 125-year role of loggers in our community.

---------------------------------------------

NOTES

1. Nancy Irene Hall. In the Shadow of the Mountain. The Courier Publishing, Enumclaw, 1983, and republished by Heritage Quest Press, Orting, 2004. p. 107.

2. "White River Lumber Company". Historylink.org. Essay 414.

3. Louise Poppleton. There Is Only One Enumclaw. 1995. p. 43.

4. Poppleton. There Is Only One Enumclaw. 1995. p. 45.

5. "Final Logs Roll Through Weyerhaeuser Mill". Kevin Hanson. Enumclaw Courier-Herald. April 30, 1990.

6. Use of Articulated Wheeled Tractors in Logging

* Current discussion of the Garrett Tree Farmer: Forestry Forum

7. "Final Logs Roll Through Weyerhaeuser Mill". Kevin Hanson. Enumclaw Courier-Herald. April 30, 1990.

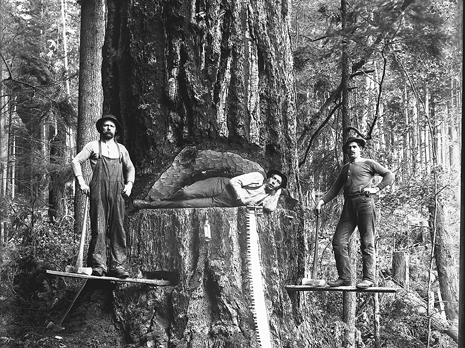

Early loggers stood on springboards to cut above the wide butt of the tree.

When pioneers first came to the Enumclaw Plateau, huge trees stood in the way of farming. They were felled by hand and most were burned because they were too big to deal with. Settlers hand split cedar for boards and shingles. William McMillan was celebrated when he built the first house here out of sawn boards, hauled from the nearest mill in Wilkeson. Johannes Mahler's lumber wagon, which also delivered the Stevensons and many of the other early settlers on the final leg of their journeys, was one of the most useful vehicles of the Plateau at the time.

Besides dealing with the massive trees in clearing land for farms, the pioneers had countless thousands of smaller logs to dispose of, but they soon discovered a use for them. Under the forest cover lay a flat, wet plateau with very little drainage. When the first roads were cut through, the mud made them impassible throughout much of the year. Miles of puncheons, logs laid perpendicular to the direction of travel, allowed uncomfortable but all-season travel. When the Northern Pacific first came to town, Frank Stevenson even felled a cedar tree across Railroad Street so people could walk over the swampy thoroughfare to his hotel.

Besides dealing with the massive trees in clearing land for farms, the pioneers had countless thousands of smaller logs to dispose of, but they soon discovered a use for them. Under the forest cover lay a flat, wet plateau with very little drainage. When the first roads were cut through, the mud made them impassible throughout much of the year. Miles of puncheons, logs laid perpendicular to the direction of travel, allowed uncomfortable but all-season travel. When the Northern Pacific first came to town, Frank Stevenson even felled a cedar tree across Railroad Street so people could walk over the swampy thoroughfare to his hotel.

Early loggers used oxen to pull the logs out of the woods. This sculpture in front of the Enumclaw Library commemorates the pioneer loggers of the area.

Because of the heavy forest cover and the need for lumber, sawmills got an early start around Enumclaw. The first one, built by Nelson Bennett, supplied timbers for the Northern Pacific bridge to Buckley, and later for other railroad bridges. Boise was the site of a mill using water power to turn the saws. Boise also boasted a shingle mill, capitalizing on the abundant and accessible cedar in the area.

Elijah Goss built the White River Lumber and Shingle Company in Enumclaw 1889, and within three years he was producing 200,000 shingles a day. (1) His sawmill was located at the site of the future Weyerhaeuser mill, with rough-cut lumber floating down a three-mile flume fed by Boise Creek to his planing mill at the edge of town. But in 1896, a fire destroyed the planing mill, and Goss sold out what was left to several partners: Carl Hanson and his sons, Swedish immigrants who already operated other mills in the area; Louis Olson, head of Hanson's logging operations; and Alex Turnbull, a Black Diamond mine mechanic.

White River Mill

Once the burned-out mill was rebuilt, the company grew quickly, shipping most of the product across the country by rail. But in 1902, fire struck again, this time burning the sawmill and all the surrounding support buildings. Even the top halves of logs in the millpond burned. The fire spread down the hill to the edge of the Plateau, but because of the townspeople's efforts and a shifting wind, the planing mill was saved. The White River Lumber Company rebuilt right away, and by the end of its first ten years in Enumclaw, it employed 500 people. (2)

Although others had used oxen, the WRLC's first logs were pulled out of the woods by horses. These were replaced soon by donkeys--giant steam-powered winches. As capacity increased and demand for logs grew, the company bought a small, wood-burning locomotive. To get it from the Northern Pacific tracks in town up the roadless three miles to the mill, workers "removed 50 feet of track from behind and relayed it to the front. They had it up there in six days." (3)

At first, the locomotive just dragged logs out of the woods right on the new tracks, but that made life short for the ties, so flatcars were hauled up from town one by one behind wagon teams. Finally, the missing rail link between Enumclaw and the White River Lumber mill was completed in 1909.

Although others had used oxen, the WRLC's first logs were pulled out of the woods by horses. These were replaced soon by donkeys--giant steam-powered winches. As capacity increased and demand for logs grew, the company bought a small, wood-burning locomotive. To get it from the Northern Pacific tracks in town up the roadless three miles to the mill, workers "removed 50 feet of track from behind and relayed it to the front. They had it up there in six days." (3)

At first, the locomotive just dragged logs out of the woods right on the new tracks, but that made life short for the ties, so flatcars were hauled up from town one by one behind wagon teams. Finally, the missing rail link between Enumclaw and the White River Lumber mill was completed in 1909.

The early winching of logs used pulleys on stumps, but in 1912, the spar pole was introduced. A man would climb a giant tree on a hilltop, saw the top off, and install rigging to yard the logs for loading. Then the train brought the logs to the sawmill. A hundred train carloads of lumber left Enumclaw each month. (4)

Steam donkeys gathered stumps for burning as well as logs for shipping to the mills.

Many of the mill workers came directly from Sweden to work for the Hansons, where others understood their language and cultural background. Most lived in camps in the woods or at Ellenson, the company housing complex up at the mill, named after Axel Hanson's daughter Ellen. Many local farmers also worked second jobs at White River Lumber Company to supplement uncertain incomes with steady wages.

White River housing at Ellenson

With greatly increased production capacity at the mill and demand for its products, the Hansons needed timber. They eventually increased their holdings to 50,000 acres. Meanwhile, Weyerhaeuser bought 900,000 acres from the Northern Pacific Railroad and became the White River's major competitor. They two companies began merging in 1909, with White River Lumber Company retaining its brand and management. (Final acquisition was not completed until 1949.) (5)

Japanese were also employed in the logging camps and at the sawmill, where they lived in their own segregated housing complex at Ellenson. They continued working for the company until the start of World War II, when they were suddenly removed to internment camps. None returned afterwards.

With the shortage of men at the time, the war also brought women into the mill workforce, and older men returned to the woods. Only the high riggers were exempted from the draft, since few had the skill for this dangerous and essential job.

With the shortage of men at the time, the war also brought women into the mill workforce, and older men returned to the woods. Only the high riggers were exempted from the draft, since few had the skill for this dangerous and essential job.

One of White River's

Japanese logging crews

Japanese logging crews

A housing boom after the war also meant boom time in logging. And not all loggers worked for White River/Weyerhaeuser. Even though the big company continued to use its railroads into the 1950s, improvements in logging trucks gave gyppos, small independent operators, mobility to reach other mills well beyond Enumclaw. Some had timberland of their own, but most bid on sales from the U.S. Forest Service or on state lands, where rail transport of logs was not allowed. With a tower (steel spar pole and winch), a skidder, a loader, and a small crew, these entrepreneurs were able to move easily from one location to another. Some used their own log trucks; others subcontracted with individual owner-operators.

The Tree Farmer skidder, a unique invention by Dwight Garrett of Enumclaw, made life a lot easier for the loggers. Son of a Black Diamond coal miner, Dwight had a fascination for machinery early. While still a student, he drove the school bus there. Later, opening his shop in Enumclaw, he developed the articulated four-wheel drive tractor that became the most efficient means worldwide for getting logs out of the woods. (6)

Early Garrett

Tree Farmer

Tree Farmer