Early Enumclaw:

The First Settlers Arrive

The First Settlers Arrive

The earliest Europeans to pass through Enumclaw were likely trappers and possibly spies from the Hudson's Bay Company. In 1841 Lt. Robert Johnson led a small group of men from Fort Nisqually on Puget Sound across Naches Pass to other forts in Eastern Washington. They were guided by two Hudson's Bay people who were already familiar with the Native American trail. The British Company was trying to encourage its own people to settle in areas north of the Columbia and prevent U.S. pioneers from doing the same. (We came that close to having Canadian accents in Enumclaw.) In 1846, the final northern border of the United States was settled, but British commercial activity continued in the Puget Sound region. The U.S. Army leased land from Hudson's Bay Company to build Fort Steilacoom as a base for protecting settlers in our area. (1)

On September 27, 1850, Congress passed the Donated Land Claim Act, which granted 320 acres to each Oregon Territory applicant who lived on his claim for four years. A married couple could receive 640 acres, a full square mile. In 1851, 58 people filed claims in what was to become Washington, 117 the year after.(2)

Also in 1850, a group of Puget Sound Settlers tried to build a wagon road across Naches Pass, but the terrain was too difficult and they abandoned the attempt. Three years later, Captain George McClellan, of Civil War fame, was sent to scout routes for wagons and rail lines over the Cascades, and to then build a wagon road over Naches Pass. When he failed, local pioneers from the Puyallup Valley and the Yakima area completed the task.

Also in 1850, a group of Puget Sound Settlers tried to build a wagon road across Naches Pass, but the terrain was too difficult and they abandoned the attempt. Three years later, Captain George McClellan, of Civil War fame, was sent to scout routes for wagons and rail lines over the Cascades, and to then build a wagon road over Naches Pass. When he failed, local pioneers from the Puyallup Valley and the Yakima area completed the task.

In 1853, Allen Porter filed the first Plateau claim under the Donated Land Act near what is now Enumclaw, taking a 320-acre piece of ground on the White River. With forest cover of huge trees, it seemed reasonable to choose one of the tribal prairies for his farm--reasonable to him but not to the 300 Smalkamish already living here. He built a cabin and barn, and did have some relations, often troubled, with his native neighbors. One of his new friends among the tribe warned him when they were preparing an attack, so he hid in the forest while they burned him out. It was an effective practice for keeping the prairies clear of the invading trees, and in this case, worked with human encroachment as well. But not for long.

Washington was organized as a separate territory from Oregon in 1853, and Isaac Stevens was named its governor. He arranged a series of councils with regional tribes for signing treaties to extinguish their title to their lands, in exchange for cash, reservations, and the right to continue using traditional hunting and fishing grounds. The treaties impacting the Muckleshoots (since they were both Duwamish and Puyallup) were Medicine Creek and Point Elliott.

Some of the signers soon decided these agreements were a mistake, while others were angry that the treaties had been offered in the first place. Skirmishes broke out on the Plateau and beyond and came to be known as the Indian War of 1855-1856, the Puget Sound War, or the Treaty War, a lot of names for a conflict that involved relatively few people over a few months.

Without a cultural concept of private property and with no way of knowing how many settlers were on the horizon, the idea of such treaties was not totally unreasonable for the tribes, especially since they could continue to hunt, fish, and gather food where they always had. However, that promise was more than a century in coming and only partially fulfilled then, and the cash payments were slow to materialize. But the trigger for retaliation was pulled when natives were attacked by settlers, whom the tribes assumed had the permission of their leaders. In tribal warfare, all members of an enemy group were often killed, regardless of age or gender. When some natives retaliated in October of 1855, nine settlers, including children, were killed in the White River Valley .

Some of the signers soon decided these agreements were a mistake, while others were angry that the treaties had been offered in the first place. Skirmishes broke out on the Plateau and beyond and came to be known as the Indian War of 1855-1856, the Puget Sound War, or the Treaty War, a lot of names for a conflict that involved relatively few people over a few months.

Without a cultural concept of private property and with no way of knowing how many settlers were on the horizon, the idea of such treaties was not totally unreasonable for the tribes, especially since they could continue to hunt, fish, and gather food where they always had. However, that promise was more than a century in coming and only partially fulfilled then, and the cash payments were slow to materialize. But the trigger for retaliation was pulled when natives were attacked by settlers, whom the tribes assumed had the permission of their leaders. In tribal warfare, all members of an enemy group were often killed, regardless of age or gender. When some natives retaliated in October of 1855, nine settlers, including children, were killed in the White River Valley .

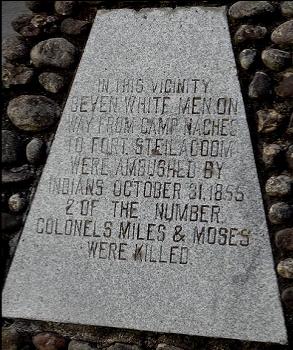

A squad of seven men from Fort Steilacoom was then dispatched, but was ambushed on Connell's Prairie, across the White River from Porter's homestead. Two of them were killed on October 27 and two more on the 31st. Another team, led by Lieutenant Slaughter, encountered a large group of the Nisqually tribe and claimed to have killed thirty, but there is some doubt about his report. What is known is that Slaughter was himself killed by natives on the night of December 3. On February 29, Chief Kanasket of the Klickitats, who supposedly killed Slaughter, was himself shot by a soldier at Lemmon's Prairie 5 (between Enumclaw and Bonney Lake). Some of the native groups dispersed while others withdrew over Naches Pass to wage resistance against settlers there. However, hostilities generally ceased west of the Cascades after the final battle of Connell's Prairie.

Two other threats further weakened the local tribes and diminished their numbers. At the same time the Army and volunteers were battling them, bands of Tlingit and Haida raiders from the north were attacking Puget Sound natives. And in 1862, a smallpox epidemic struck the tribes, who had no resistance to the alien microbes of the settlers. (6) The stage was now set for rapid development on the Enumclaw Plateau, even though by 1860 the total white population in King County was only 305. (7)

Two other threats further weakened the local tribes and diminished their numbers. At the same time the Army and volunteers were battling them, bands of Tlingit and Haida raiders from the north were attacking Puget Sound natives. And in 1862, a smallpox epidemic struck the tribes, who had no resistance to the alien microbes of the settlers. (6) The stage was now set for rapid development on the Enumclaw Plateau, even though by 1860 the total white population in King County was only 305. (7)

Connell's Prairie today

NOTES

1. Lt. Johnson's Account of the Naches Trail, 1841 NOTES

2. http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=400%20%20

3. http://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/Enumclaw,_Washington.html

4. http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/seattle55.htm%20

5. http://stories.washingtonhistory.org/leschi/slaughter.htm

6. http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=5171

7. http://your.kingcounty.gov/kc150/1860s.htm